This edition includes topics such as retirement crises, life hacks, social media reduction, and climate change.

A few wonderful thoughts

This wonderful post on lichens starts with two profound quotes:

“When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe,” the great naturalist John Muir wrote in the middle of the nineteenth century. “We forget that nature itself is one vast miracle transcending the reality of night and nothingness,” the great naturalist Loren Eiseley wrote a century later as he considered the meaning of life. “We forget that each one of us in his personal life repeats that miracle.”

As an aside, the lyrical writing of Maria Popova is a joy to read. I hope I can write 1% as well as she can one day. If you are not reading her writing, what the hell are you doing in life? Also, I just bought her book Figuringa few days ago, I can’t wait to devour it.

I found these two gems in Kris Abdelmessih’s wonderful newsletter:

Paul Bloom on choosing your suffering:

It may be the major theme of my book–is about the importance of chosen suffering. I have a very different opinion about unchosen suffering, we can talk about that. The importance of chosen suffering is part of a good life, which is, I think the projects that make life worth giving[?] involve suffering. We often know this ahead of time.

And, having kids is such an example. For one thing in having kids, at least for me–maybe I’m prone towards anxiety–is really an experiment in feeling mild dread for the rest of my life. Loving such fragile creatures–and they remain fragile even into their 1920s–it is like there is a hangman’s noose sitting around your neck all the time.

And then they will separate from you. If you do it right, if you are lucky and if you’ll do it right, these creatures that you love and devoted your life to, will leave you. And, actually, if you do it right they will think a lot less about you than you will think about them. Because[?] they’re into their own lives. It’s such a perverse project. And I think it’s a very human one.

This video is a succinct summary of choosing your suffering. The idea is from his book The Sweet Spot, I’ve yet to read the book but it’s on my wish list:

BTW, there seems to be a risk free arbitrage opportunity or Amazon is fooling us.

This reminds of one of my favorite Jerry Seinfeld quotes:

Someone says to you “Oh you have it so easy. You’re so naturally funny and blah blah blah.” Yes, you are naturally funny and you do have that ability to figure that stuff out. But they don’t realize the amount of work that goes into it. It’s like going into the gym every day. It’s hard, you know how you walk in every day and you go “Oh geez I gotta do this again.” Yeah it sounds like a tortured life and you say it is, it is, it is. But you know what your blessing in life is? When you find the torture you’re comfortable with – courage, it’s kids, it’s work, it’s exercise. Yes it’s not eating the food you want to eat. Right, find the torture you’re comfortable with and you’ll do well.

Kris Abdelmessih on responsibility:

b) Get to having real responsibility as fast as possible

Responsibility = risk and risk accelerates learning. A little more responsibility than you think is appropriate will stretch you — if you want to rise to that you likely will. If you don’t feel stretched, even if you’re making good money, the human capital part of your ledger is being docked. Rest-and-vest attitudes are deceptively expensive in the long run — don’t ever adopt one in your 20s and 30s (and probably not after that either).

A few bangers from Jim O’Shughnessy’s tweet full of bangers:

“A good way to discover your shortcomings,” said the Master, “is to observe what irritates you in others.”

“Live your life as you see fit. That’s not selfish. Selfish is to demand that others live their lives as you see fit.”

“Seek to change yourself, not other people. It is easier to protect your feet with slippers than to carpet the whole of the earth.”

“If people want happiness so badly, why don’t they attempt to understand their false beliefs? First, because it never occurs to them to see them as false or even as beliefs. They see them as facts and reality, so deeply have they been programmed.”

I liked this post about lifehacks by Alex Guzey

seek ground truth and poke reality. don’t settle for proxies or for winning arguments.

never defer key beliefs. do everything possible to find ppl thinking from first principles rather than from what’s reasonable or what someone else believes

be suspicious if you haven’t felt awkward today

ppl good at thinking think that thinking is everything; people good at doing think that doing is everything. doers dismiss thinkers & thinkers are scared of doers.

if there’s something on your mind, write it down & get it out. maintain full attention on what you’re doing.

if you did a sequence of actions 3 times, make a checklist

if you have a thought and you don’t like it, you can tell your brain that you don’t like it and drop it.

add questions & ideas you want to get back to later to anki, snooze tabs, schedule them in asana.

if you’re not failing you’re not operating at the edge. if you’re not operating at the edge, you’re not learning as much as you can

Unpublic whispers

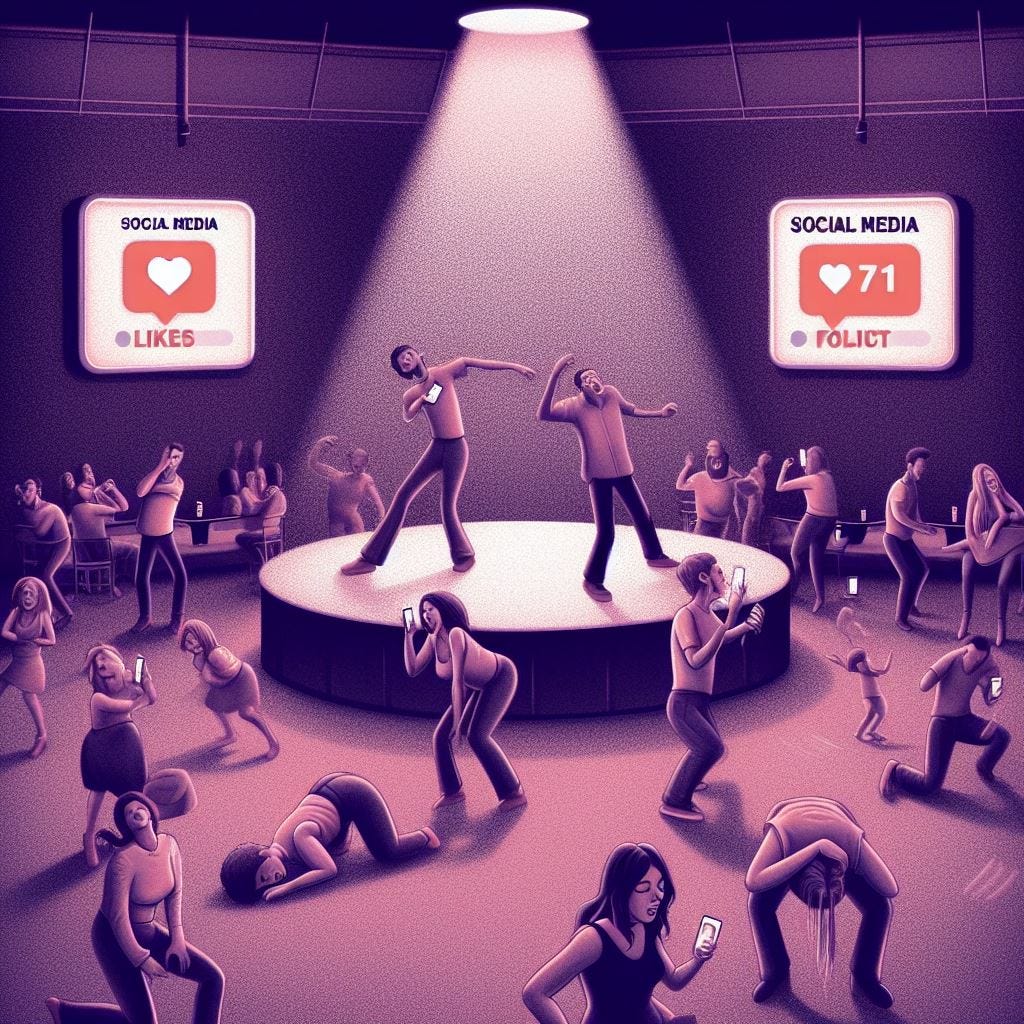

To reiterate what I wrote in a previous post, social media was fun, but it isn’t anymore. It’s become a performative hellscape where we’re all twerking and grinding for a “couple Elon bucks,” as Ryan Broderick put it elegantly. Opening Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn leaves you with a nauseating feeling—everything is just fake, plastic, airbrushed horseshit. Twerking—too much twerking—for likes and shares.

The greatest trick these platforms pulled was letting an entire generation delude themselves into thinking that they weren’t debasing themselves by twerking at the altar of attention. I say this because I’m no saint; I’ do my share of twerking and grinding.

I’m writing this because I came across two brilliant posts by Thomas Bevan.

The End of the Extremely Online Era

The consequences of life lived online have bled through into the real world and this has happened because we have allowed them to. It’s a cliché to say that real life is now a temporary reprieve from the online, as opposed to the other way around. We pay the price for all of this via boarded up shops, closing pubs, empty playgrounds and silent streets as each individual stays at home each night, enchanted by the blue flicker of their own little screen feeding them their own walled in world of news and content and edutainment.

I believe it will end, this so-called way of life. Not through the Silicon Valley oligarchs spontaneously developing a conscience or being legislated into acting with a modicum less sociopathy. I don’t believe people will be frightened into changing how they act or suddenly shamed into putting their phones down for once in their lives. Such interventions don’t work with most addicts and more and more people are legitimately hooked on their devices than we are currently willing to countenance. No, I think this will all end, as T.S Eliot said, with a whimper. People will simply lose interest and walk away. Because the internet now is boring. People spend all day scrolling because they are trying to find what isn’t there anymore. The authenticity, the genuinely human moments, the fun..

We can do what we want here. We’ve always been able to. The first step is admitting how bad things are (it’s no accident that by far the most popular thing I have ever written is about how dull and unsustainable this Extremely Online era is. I touched on something many have felt but not articulated). Our arts and culture are not good enough. We’re not good enough, and so there is no misunderstanding I say that in a spirit of love and encouragement. We are, both collectively and individually, capable of so much more than frenetically edited youtube shorts and trend chasing and parasocial relationships with influencers and impotent moaning about the present and rose tinted nostalgic longing for some pre smartphone past. We could be so much more. We could create art that is so much more truthful and searching and humane and ambitious (and that is also fearless and angry and rabble-rousing if need be).

These two posts capture my own vibes about being online. It just isn’t fun anymore. Ok, that’s a lie. It feels good when I am shitposting, but that dopamine rush quickly wears off, and it all starts being shit again. I’m not saying we all should rise up like the Luddites and smash our modems and slash our LAN cables like they did handlooms and head toward the forests. I think you can still be online without having to feel terrible, and it starts with being a little mindful of what we consume. Otherwise, we will be consumed. Being online can’t be at the expense of a divorce from the real world. In other words, pick your rabbit holes carefully—this website is my attempt at it.

Anyway, this bit stood out in the second post:

we have ways of meeting in private groups and hanging out and talking to each other via video as a prelude to meeting face to face.

The observation is spot on; people don’t seem to enjoy posting and sharing things publicly. It shows up in the the data as well.

We find that many measures of open participation, such as sharing and commenting, have declined across countries, with a minority of active users making most of the noise. Looking back, we can detect a period of peak sharing in some markets between 2016 and 2019, primarily driven by Facebook and by divisive events such as the election of Donald Trump in the United States, the Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom, and the vote on Catalan independence in Spain. But since then, online participation has shifted to some extent into closed networks such as WhatsApp, Signal, Telegram, and Discord, where people can have private or semi-private conversations with trusted friends in a less toxic atmosphere.

The first time I noticed this trend was when I was writing a previous post on the travails of news publishers.

Public feeds of all social platforms are filled with garbage from “influencers” and “creators.” It’s just a sea of rote, anodyne, regurgitated bullshit out there. Add to this the relentless toxicity of the platforms, people seem to be spending more time in messages and private chat groups than share on public feeds. Even the head of Instagram admitted as much a few months ago:

Outside of TikTok, Mosseri is eyeing another competitor: encrypted messaging platform Telegram. Most of Instagram’s growth has been in stories and DMs, Mosseri said on the podcast. Mosseri has shifted resources to messaging, he said. “Actually, at one point a couple years ago, I think I put the entire stories team on messaging,” Mosseri added. DMs are also crucial for younger users. “If you look at how teens spend their time on Instagram, they spend more time in DMs than they do in stories, and they spend more time in stories than they do in feed,” Mosseri said. Young users below the age of 20 are also actively using Instagram’s Notes feature (think Y2K era AIM status), prompting new conversations and driving up overall engagement on the app among teens, Mosseri said. “But, the thing is, we’re not a messaging app,” Mosseri noted.

This is an interesting shift in how people are interacting on platforms. The implications for brands and marketers are obvious, but what it means at a larger level is anybody’s guess. On an interesting note, the activity on Substack Chat seems decent. It’s not as much as Twitter, but it’s much slower and saner than Twitter. I’ve no idea about the numbers, but it’ll be interesting to see Chat becomes popular.

On that note, here’s the link to my chat.

On a related note.

If you are in the market for a fresh and brand new reason to feel like shit, check your phone for stats on how many hours you use it in a day. Now, do the math on how much time you spend glued to your phone screen in a year. Immediately after that, let your sub-conscious human brain do what it does best: come up with rationalizations that you do plenty of useful things other than rage tweeting or subjecting the world to your narcissism on Instagram. After that, let your conscious brain murder your rationalizations, and you have my permission to feel like shit.

Josh Drummond on smartphone addiction

Yet. These days, as I scroll, it’s accompanied with the feeling that I’ve been conned. Looking at the numbers, it’s clear: I’ve spent more than a year of my life on smartphones and the return on investment is terrible. You could excuse the sheer amount of time spent if there’d been something to show for it — a big social media presence, the ability to code, learning a language on Duolingo, a consistent output of pretty much anything creative. But I can’t make any of those claims. I know life is about much more than “productivity,” but even with that caveat my phone time is staggeringly unproductive. I post perhaps twice on Bluesky or Mastodon on a big day. Instagram is maybe once a week. Nearly all the time I spend on my phone (and, if I am being honest, my computer) is in passive consumption. Lurking. I don’t have many good memories of the half of my life I’ve spent on screens, or in fact any strong memories at all; it’s all one amorphous, algorithmic blob of memes and blogs and socials and takes.

Good reads

How the Story of Soccer Became the Story of Everything

A good timeline of how shady billionaires, and private equity funds took over soccer.

Just as the Moneyball era produced a generation of baseball fans who talked like Nate Silver, soccer’s age of decadence has turned fans into current-affairs obsessives. Sovereign wealth funds, sanctions, and debt seep into Saturday-morning chatter with the same frequency as counter-pressing or expected goals. The forces shaping modern soccer into something bigger, better, and more morally bankrupt than ever are the same ones that have blown up everything else. Following the sport is an education in oligarchs, oil, corruption, media, partisanship, politics, and the financialization of everything. You don’t even have to like soccer to learn from it—because in a lot of ways, the story of the sport’s last two decades hasn’t been about soccer at all.

Every month you work, you save a part of your paycheck to be able to retire at 60–70, kickback, and enjoy the sunsets. But increasingly, it’s becoming obvious that the traditional notions of retirement are flawed and a mirage. The biggest problem is that people are living longer than ever, which means they need a whole lot more money to get by from 60 to 90 or 100. Then there’s the issue of ageism, even as countries around the world face a demographic crisis that is leading to worker shortages. Old people can’t find work, even if they want to. Then there are the underappreciated issues of longevity: we can’t live alone because we’re social creatures. As the often-repeated cliche goes, loneliness is as bad as smoking and obesity. This is a brilliant piece looking at the many problems of the retirement system and the challenges retirees face.

HERE’S A BLEAK prospect for many retiring Canadians: they will leave or be pushed out of the workforce too soon and without enough money. They’re financially prepared for the short and medium haul of life after work, but not the long one. They will go on to live too long, in too poor health (increased life expectancy has also increased the number of years people spend being sick), with a dwindling ability to support themselves or live independently. Ultimately, they’ll become wards of the state, housed in long-term care at great cost to the government and society. Sinha said: “This is where our destitute end up, in these government-run facilities.” According to a 2019 report by the National Institute on Ageing at Toronto Metropolitan University, long-term care costs are expected to triple from $22 billion to $71 billion by 2050. “It will be the equivalent of the modern-day Victorian poor house for our old,” Sinha said.

Pair this post with:

An ageing country shows others how to manage

This means finding ways for old people to keep working. Nearly half of 65- to 69-year-olds and a third of 70- to 74-year-olds have jobs. Japan’s gerontological society has called for reclassifying those aged 65-74 as “pre-old”. Ms Akiyama speaks of creating “workplaces for the second life”. But the work of the second life will differ from that of the first; its contribution may not be easily captured in growth statistics. “We have to seek well-being, not only economic productivity,” Ms Akiyama says. Experiments abound, from municipalities that train retirees to be farmers, to firms that encourage older employees to launch startups. The elderly “want dignity and respect”, says Matsuyama Daiko of the Taizo-in temple in Kyoto, which has a “second-life programme” that offers courses for retirees to retrain as priests.

This widespread insensitivity of the rich, who have protected themselves against the economic hardships suffered by the lower 90 percent, is discouraging, and does not portend well for long-term social stability. It is extremely short-sighted and incompatible with the America that much of the world has come to admire and wishes to replicate.

The answer does not lie in invoking protectionist policies of the past. Globalization, as Freeland suggests, is irreversible. Rather, it lies in adjustment policies, which means a much better educated workforce, and social protection for those too old to adjust and recycle themselves into other decent-paying job opportunities. But this is a costly project, and the abhorrence of the rich for paying taxes makes this a serious challenge, especially in the United States. Freeland touches on all these points and properly lays great emphasis on quality education.

Global temperature hit upper circuits

“The ERA5 record now contains two days where global temperatures exceed the pre-industrial level by more than 2°C. That this should happen in the same month that world leaders will gather to take stock of progress towards meeting Paris Agreement commitments at COP28 sends a very clear message – the time for definitive action to tackle climate change is now,” said Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Director Carlo Buontempo. “While exceeding the 2°C threshold for a number of days does not mean that we have breached the Paris Agreement targets, the more often that we exceed this threshold, the more serious the cumulative effects of these breaches will become,” he added.

How 2023 scorched our dinner plates

While the price action on temperature is bullish, there’s a tiny issue: we might starve to death. Otherwise, it’s all good.

A depressing summary of how rising global temperatures are affecting everything from soy, corn, and wheat to blueberries and olives.

TLDR: It ain’t good; we’re going to die.

This year added another spicy ingredient: Some of the hottest temperatures ever recorded on Earth. Extreme heat in 2023 diminished wheat yields in India, while drought took a bite out of rice in Indonesia. Disasters worsened by rising average temperatures also took a toll. Cyclone Freddy tore up fields of corn, rice, and beans across Malawi in March, the brunt borne by small subsistence farms. Severe weather also took a toll on livestock. Heat and drought stressed cattle herds across the US, Heads of cattle were already at their smallest numbers since records began in 1971. It’s even making cows produce less milk.

As if this wasn’t cheerful enough, climate change is impacting maritime trade as well. Again, if you are a glass-half-full person, you can argue that ships are the biggest source of emissions, and less ships going around is good.

But

80% of global trade by volume is carried on the seas. So, we might just starve.

Apart from that, it’s all fine.

As the Chart of the Week shows, ports in Panama, Nicaragua, Ecuador, Peru, El Salvador and Jamaica are suffering most from these delays, with 10 percent to 25 percent of their total maritime trade flows affected. But the drought’s effects are felt as far away as Asia, Europe and North America. The drought will hamper trade for months to come, with canal passages set to halve to 18 ships per day by February, down from 36 in ordinary times. Economies reliant on the canal for trade should prepare for more disruption and delay.

But.

You can either be a glass-empty guy and die of despair even before we are slowly cooked like charcoal chicken or make some money. Climate change can be good for your portfolio.

Chartbook Carbon Notes 7 – The IEA’s message to the oil and gas industry: wake up!

A brilliant post by Adam Tooze decoding the International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook.

Either the oil and gas industry is silently gambling that the energy transition will not happen, that we remain in the so-called STEPS scenario, which spells disaster for the planet. Or, if one assumes that current trends continue and politics and other non-fossil business interests are now driving an inexorable energy transition, then one can hardly avoid the conclusion that the titans of the oil and gas sector are burying their heads in the sand. It is not the green energy advocates but the fossil fuel holdouts who are losing their grip on reality.

Pair this with, a summary of the report.

I reject the premise of this post. On a daily basis, if you are not eating a minimum of 250 grams of supplement pills, perineum sunning (sunbathing your butthole), rubbing the hide of a dead rat on your thigh, and drinking your own urine, do you even care about your health?

For immune health, some influencers seem to think the Goldilocks philosophy of “just right” is overrated. Why settle for less immunity when you can have more? Many social media posts push supplements and other life hacks that “boost your immune system” to keep you healthy and fend off illness.

Because sustaining immune balance is critical, tinkering with the immune system through the use of supplements is not a good idea unless you have a clinical deficiency in certain vital nutrients. For people with healthy levels of nutrients, taking supplements could lead to a false sense of security, particularly since the fine print on the back of supplements usually has this disclaimer about their listed benefits: “This statement has not been evaluated by the FDA. Not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.”

Ridley Scott would’ve made a kick ass historian 😂

But don’t think that insulting an entire country is enough for Scott. Speaking to the Sunday Times’s Jonathan Dean last weekend, he also reserved some ire for historians, some of whom have suggested that Napoleon might not be the most rigorously accurate film ever made. Scott responded by addressing the entire historian community. “Excuse me, mate, were you there?” he raged. “No? Well, shut the fuck up then.”

The wine is still going down a treat and our conversation meanders wildly, from whether aliens exist (‘I think we’ve been monitored for years!’ roars Scott. ‘How did the Egyptians build the pyramids? Rolling 20-tonne stones on logs? F*** off!’) to the dangers of AI: ‘We’ve got to step on this shit now, and move forward with incredibly tight constraints. — The Standard

From my swipe file

I have a swipe file where I collect interesting links, quotes, etc. Here are a few things I added to it this week:

The Dalai Lama should’ve been a rapper. I came across this long quote on Tony Isola’s wonderful blog:

“We have bigger houses but smaller families; more conveniences, but less time; We have more degrees, but less sense; more knowledge, but less judgment; more experts, but more problems; more medicines, but less healthiness; We’ve been all the way to the moon and back, but have trouble crossing the street to meet the new neighbor. We’ve built more computers to hold more information to produce more copies than ever, but have less communications; We have become long on quantity, but short on quality.

These times are times of fast foods; but slow digestion; Tall man but short character; Steep profits but shallow relationships. It is time when there is much in the window, but nothing in the room.” ―Dalai Lama XIV

“To feel most beautifully alive means to be reading something beautiful, ready always to apprehend in the flow of language the sudden flash of poetry.” ―Gaston Bachelard

That’s it for this week. Go and suffer a little.